Today’s “Culture Wars,” as Wilber points out in the Ken Show interview (which we will be reviewing), are actually a War of Worldviews. These include Traditional-Conservatives who emphasize order, authority, and continuity with the past. For example, “Make America Great AGAIN” (which is a dog whistle for “making America white again”) is one current manifestation in politics. Wilber labels this stage-structure (or cultural meme) with the color “Amber” (“Blue” in Spiral Dynamics), emphasizing traditional religions and authoritarian structures. It comprises approximately 30-40% of the global population (as of the early 2020s) and 25-30% of the US population (see where MAGA resides?). Jean Gebser (and Wilber) identify this worldview as being rooted in the Mythic-Membership past of “ethnocentric” (or group identity) cognition, united in shared myths and beliefs. Therefore, it is also known as Traditionalism, the oldest worldview in today’s society (other than the very small percentage of “Red” tribalism).

It’s important to remember that Gebser’s structures are not just developmental but are ontological mutations in consciousness (i.e., each structure reshapes our perception of time, space, self, and world). Today, Amber is primarily active in today’s “The Right,” which prefers resistance to big government (for example, the feds correcting intolerant behavior, such as racism), any form of socialism or welfare (or government assistance), and even resists secularism (or the separation of Church and State). Currently, this includes the rise of white Christian nationalism, which is an attempt to nullify the advances of the civil rights movement and secular governance (such as a woman’s right to an abortion). The danger of this structure, especially when dominating government affairs, cannot be overstated; it is crippling humanity’s progress to higher, more inclusive levels of development. Nonetheless, like all worldviews, it contains positive qualities that should be incorporated into the higher structures of consciousness development, such as community cohesion, stability and order, loyalty and duty, and cultural preservation.

This worldview is opposed by “The Left,” also known as Modern-Liberals, who emphasize individual rights, equality under the law, free markets, free trade, and democratic governance. Since this worldview emerged during and after the Western Enlightenment (following the 17th century), it emphasizes personal liberty, property rights, secular governance, scientific reasoning, and rational progress. It comprises approximately 30-40% of the global population (as of the early 2020s) and 35-40% of the US population. Wilber labels this “Orange” or Modernism (modernity). Both Wilber and Gebser point out that this worldview is rooted in the Mental-Rational structure (coming into force after the Renaissance, with deep roots in ancient Greece and the Axial Age). Wilber identifies this stage-structure as “worldcentric” since democratic and “universal rights” are the dominant paradigm in Orange-Modernism. However, I take issue with this view since I feel the next stage of “Green” is actually more “worldcentric” than Orange due to its advanced pluralism with global reach, so let’s call Orange more “nation-centric,” a form of we-centered patriotism—E pluribus unum—“out of many, one.”

Wilber was correct in the interview to point out that the terms “Left” and “Right” originated during the French Revolution in 1789, when the newly formed French National Assembly convened to draft a constitution. Members were naturally divided in where they sat in the assembly building based on their political attitudes, which became symbolic of their broader ideological differences:

· Those who supported the monarchy, aristocratic privileges, and the established order, including tradition, hierarchy, aristocracy, religion, and social order, sat on the right side of the president (chair) of the Assembly.

· Those who supported revolution, secularism, and radical change—typically favoring equality, democracy, and the abolition of privilege, thus supporting liberty, equality, secularism, and reform—sat on the left side.

By the 19th century, the terms were used throughout Europe to categorize ideologies, where the “Left-wing” represents progressives, socialists, communists, and later social democrats (which is why the GOP currently uses these terms in a denigrating way). The “Right-wing,” on the other hand, represents conservatives, monarchists, traditionalists, authoritarians, and eventually fascists (though fascism is a complex form of authoritarianism). In modern democratic systems, the terms further evolved to include “Center-Left” and “Center-Right” positions, reflecting more moderate stances. In contemporary usage, the terms “Left” and “Right” are used worldwide, but their meanings vary depending on the context. For example, in the United States, the Democratic Party is generally considered center-left, while the Republican Party is center-right to right-wing (and, under Trump, even far-right). In Europe, the terms “Left” and “Right” often imply social democratic or even socialist policies, whereas “Right” can encompass both free-market liberalism and cultural nationalism. These variances must be taken into account. Each person—everyone—must decide which “side” you want to support. It should be obvious which position is more integral or highly evolved and is committed to advancing evolutionary progress (a genuine hallmark of being integral).

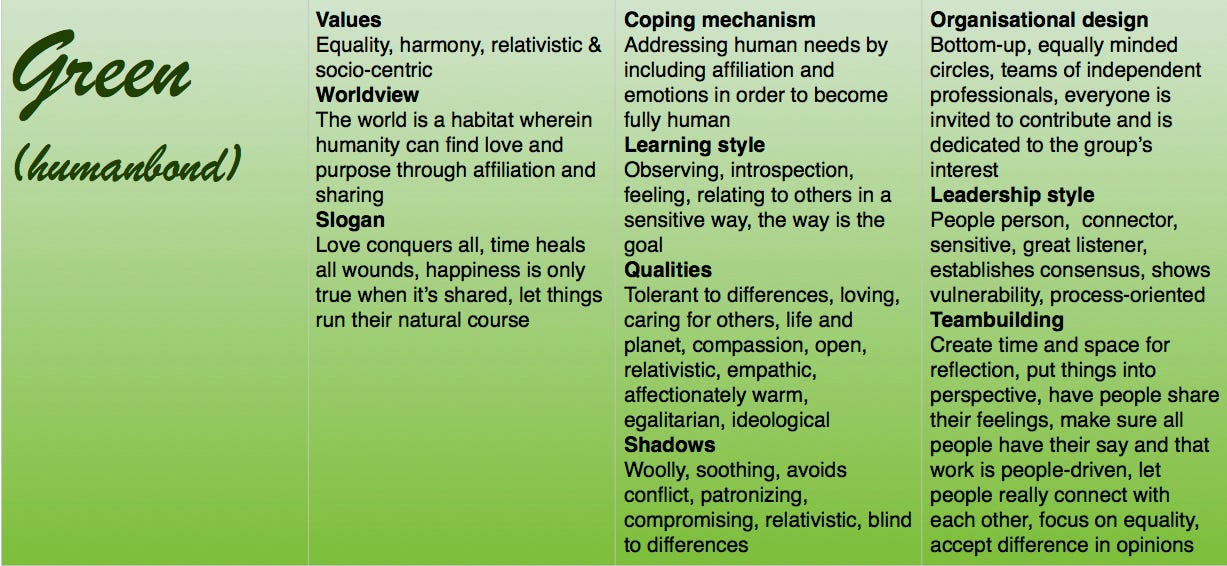

The latest stage-structure or worldview to emerge in the 20th century is the Liberal-Progressives (a further extension of modern liberals) who emphasize progress—moral, economic, and technological. They focus on social justice, expanded democratic participation, and equitable distribution of resources and opportunity. It comprises approximately 10-15% of the global population (as of the early 2020s) and 15-20% of the US population, which is why it has difficulty gaining political power. Wilber labels this worldview “Green” Postmodern Pluralism, or what Gebser identifies as an “efficient” Mental worldview (whereas “rationality,” according to Gebser, is a “deficient” form of the Mental structure). Green can therefore be seen as an early form of Integral, but Gebser did not use these designations (used by Spiral Dynamics and Wilber’s model). In my view, Green represents the first phase toward becoming “Integral” (or “Teal/Turquoise”) with its inclusive emphasis on pluralism and environmental protection. The “Green postmodern” worldview—dominant in universities, media, and activist groups in the West—is often overrepresented in cultural influence compared to its actual global population percentage.

According to Wilber (following Clare Graves and Spiral Dynamics), Green is the final stage of the so-called “1st-Tier” worldviews (from Archaic survivalist to Green postmodernism). This is where Wilber’s strong critique of Green comes in: he claims that Green is still 1st-Tier because it doesn’t recognize developmental hierarchies based on his definition of “Integral,” which is the first stage entry into “2nd-Tier” consciousness. I tend to question the rigid boundaries and definitions surrounding these “Tiers,” since I see developmental structures as more fluid than Wilber tends to portray them. For example, “Deep Green”[1] (or healthy Green) and its pluralistic and inclusive attitude demonstrate that it recognizes “natural hierarchies” or the natural unfolding of evolution and societies, yet without privileging any one stage or group over the other. However, Wilber rejects this position (since his allergy to Green seems to misunderstand them).

However, Green does in fact reject rigid social hierarchies, or what Wilber calls “dominator hierarchies,” such as patriarchy (where men dominate women), governmental hierarchies, including monarchies (where inherited royalty and the upper classes dominate the lower classes), and authoritarian regimes (where the ruling elites dominate those being ruled). I feel a good argument can be made that “Green” is actually “Early Integral” (as I’ve suggested)—thus, making “Teal” middle-Integral and “Turquoise” advanced-Integral. The Teal/Turquoise or “Integral” worldview is still emerging, comprising approximately only 1-2% of the global population (as of the early 2020s) and 2-4% of the US population. They tend to be associated with meta-theoretical thinkers, late-stage spiritual practitioners, and some organizational pioneers; thus, they have little to no representation in organized politics (unfortunately).

Another view that addresses Green postmodernism in the current climate of Integral theorizing is Metamodernism, particularly as framed by Hanzi Freinacht in The Listening Society (2017). Both Integral Metatheory and Metamodernism share many overlapping values but also critical differences. They both attempt to map developmental worldviews and make sense of cultural evolution—but with distinct emphases, philosophical foundations, and political implications. They both view Green as having many positive strengths, such as pluralism, equality, environmentalism, and social justice; yet also exhibit several limitations, including relativism, an emotional immaturity that tends toward narcissism and a victimhood identity, cultural fragmentation, and political impotence. Both agree that Green postmodernism is necessary but insufficient for future evolution; therefore, they both offer solutions for higher development. Metamodern theory has strong resonances with Ken Wilber’s Integral vision, particularly the concept that society must evolve in both its internal and external aspects (in all the “quadrants”). However, Freinacht places more emphasis on political structure, emotional intelligence, and inner child development, whereas Wilber focuses on psychological health (or “growing up” and “cleaning up”), and meditative spiritual states (or “waking up”).

Metamodernism attempts to explicitly synthesize modern and postmodern values. Some see Hanzi’s “Metamodern” stage as roughly equivalent to early Integral-Teal (not yet Turquoise), but better grounded in sociopolitical structures and realpolitik than Wilber’s spiritually-anchored model. They are similar in their complexity, integration of paradox, and global care, while Hanzi focuses on emotional depth, political systems, and future-ready governance. Wilber, on the other hand, grounds development in spiritual depth and perennial wisdom. In my opinion, for all the strengths of the Metamodern movement, including its playfulness and irony, its lack of spiritual cohesion (other than honoring spiritual practices) is its weakness. Therefore, it is not fully Integral. Nonetheless, it serves as a valuable bridge to move beyond the conflict between modernity and postmodernity, or into a post-postmodernism, as it’s sometimes referred to. Both are united in diagnosing the current limitations of modern and postmodern societies and offer a vision for a future society that is more emotionally, psychologically, developmentally, and spiritually attuned.

In addition, in my opinion, we must never forget that Enlightenment or God-Realized consciousness, the most-evolved stage or structure in the spectrum of consciousness, should be the final arbitrator (or guide) for social politics. This is because all of the other stages (personal and collective) are limited, incomplete, and still egoically-driven. Wilber hardly ever mentions this anymore in his political reviews, although he has addressed it before in earlier books.[2] In other words, Integral itself is still only “true but partial,” as are the worldviews of Green-Progressives, Modern-Liberals, and certainly Traditional-Conservatives. If we support the ongoing evolution of consciousness in individuals and society, we must be willing to grow into and beyond all the lesser stages in the spiraling dynamics of the spectrum of consciousness. Ultimately, true human wisdom only comes from realizing Nondual Divine Enlightenment and living from that state-stage of awakening. Then we can “reenter the marketplace” (or “showing up”) with the insightful skillful means necessary to establish a just society for all.

I should also mention the value meme called “Red,” or the “Magical-Mythic” worldview, since Red–Amber–Orange makes up approximately 75–80% of the global population (Red is approximately 10% of the global population and around 8% of the US population). This level of development is associated with power, dominance, and impulsive survival needs. It tends to be egocentric and exploitative, viewing the world as a jungle (or battlefield) where only the strongest and mightiest survive, while the weak are subjugated. This includes, for example, warlordism, gang culture, some authoritarian subcultures, street-level violence, and reactive politics. In short, it is a form of brute tribalism (although this view does not encompass the more evolved capacities of indigenous tribes for mythic cohesion, sustainability, and environmental reverence, which are reflections of higher stages of development). Obviously, most wars and violence originate from this level or value meme in viewing the world, although they often use the technologies of more advanced thinking. When people or tribes or states or nations go to war, they have regressed to Red power dominance.

In short, the United States has a higher percentage of the population in Orange and Green than the global average, due to its economic development and cultural diversity. Everyone and every collective (whether tribe, state, or nation) has a “center of gravity” or mean average since all the various worldviews and stages of development tend to be psychically active in the human psyche. Nonetheless, we tend to live within a particular developmental stage or worldview as we progress through the fluid and spiraling spectrum of consciousness. Amber is declining slightly in the U.S., though it is still dominant in rural areas, and active in many political factions such as MAGA, which currently rules a large part of Congress and the White House (where its Red tendencies will draw the US into war, including on American streets, such as with ICE). Teal and Turquoise are growing fastest in educated, cosmopolitan areas—found among systems thinkers, conscious entrepreneurs, and transdisciplinary leaders. Whereas, Violet and Clear Light (or the higher transpersonal levels) refer to state-stages or “structures” of mysticism and enlightenment, which transcend conventional egoic development. These are rare but crucial for spiritual evolution and the fulfillment of humanity’s potential and capacity.

“Neoliberalism” is another term I should mention, for I always found this confusing since it’s not a new form of Left-wing Liberalism, but is an economic policy that emphasizes deregulation, privatization of social services, austerity (i.e., balanced budgets), and free trade (thus is associated with globalization). In other words, it favors more traditional, Amber-oriented authority power structures than liberal values. It is not a worldview but an economic view in reaction to Keynesian economics (used since WWII) that included government-managed economies and welfare states. Thus, neoliberalism straddles both Traditional-Conservative (Amber) and Modern-Liberal (Orange) worldviews, as it has been supported as a policy by Conservatives like Margaret Thatcher (UK) and Ronald Reagan (US). Neoliberalism was also adopted by Liberals like Bill Clinton (US) and Tony Blair (UK), and was called the “Third Way.” It expanded globalization (as seen with NAFTA and the WTO), which tended to serve corporate elites and profits, rather than the working class (a trend that contributes to the current middle-class financial crisis). Today, contemporary Green-Progressives, including figures like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (and others), strongly criticize corporate capitalism and neoliberal Democrats for abandoning the working class and strengthening the upper, wealthy classes, contributing to vast income inequality.

I should also mention another important term discussed in the interview, “Postmodern Relativism” or simply “Relativism,” which is a philosophical and cultural stance that emerged prominently in the mid-to-late 20th century, particularly within postmodern thought. It challenges the Enlightenment ideals of objective truth, universal reason, and foundational knowledge by asserting that truth is relative to cultural, linguistic, historical, or individual perspectives. Key aspects of postmodernism, which are most evident in the Green worldview, include skepticism toward meta-narratives or grand, totalizing stories, such as Wilber’s Integral Metatheory, which claim to explain all aspects of reality (this is one reason why Wilber despises Green). Relativism focuses on a pluralism of truths since no single viewpoint has privileged access to what is actual “reality” and, therefore, promotes the deconstruction of authority in meaning, language, and social norms.

Therefore, relativism asserts that identity and subjectivity are socially constructed, not essential or fixed (hence leading, for example, to the gender and transgender issues in today’s world). This also gave rise to today’s highly criticized “Identity Politics,” which refers to political positions or movements that are based on the interests and perspectives of social groups with which people identify—such as race, gender, sexuality, religion, ethnicity, or nationality—especially those that have been historically marginalized or oppressed. Identity politics typically arises in response to systemic discrimination, exclusion, or oppression, thus placing an emphasis on belonging to a particular social group (e.g., Black, LGBTQ+, female, Indigenous, etc.), often based on lived experience (not merely theories). This view, obviously, strongly grates against Traditional Amber values and even Modern Orange thinking. Consequently, Identity politics is both a form of political organization and a theoretical stance that centers identity as a critical factor in justice and representation. It remains a contested but powerful force in contemporary social and political discourse and helped fuel Trump’s re-election, as Traditional-Conservatives (Amber) are strongly opposed to any variation on traditional norms. In this case, as Wilber emphasizes in this interview, these conflicts are at the fundamental core of today’s Culture Wars.

Postmodern relativism, or the “Green” worldview, gained traction in academia since the early 1960s—especially in literary theory, anthropology, gender studies, and cultural studies—before seeping into broader cultural narratives. These views became embedded, for example, in DEI (or “diversity, equity, and inclusion”) policies, which are used by universities, the government, and corporations to help address the inequities of the past. Trump and his current policies, however, are aggressively attacking these postmodern views of Green Pluralism; thus, the far-right can be viewed as regressive or trying to nullify over 50 years of progress. Postmodernism is often critiqued for leading to moral relativism or epistemological nihilism, or what philosopher and cognitive scientist John Vervaeke terms the “Meaning Crisis.” Today’s GOP has weaponized the concerns of oppressed minorities, such as Black Lives Matter, via the term “woke” or the “woke virus,”[3] not understanding or appreciating what “woke” meant initially, which is to be awake or aware—or “woke”—to racial injustice, discrimination, and social inequality.

An insightful book I’ve been reading lately, Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire—A 500-Year History (2017) by Kurt Andersen, is a cultural history and critique of how

American culture became untethered from a shared reality, tracing the roots of magical thinking, anti-intellectualism, and conspiracy culture. He points out that Postmodern Relativism emphasizes subjective truth over objective facts. He critically reviews how America’s religious individualism, frontier mythology, and entertainment culture nurtured fantasy over reason, offering a timeline from Puritan theocracy to New Age spirituality to Donald Trump, arguing that America has always had a weakness for belief over evidence. Andersen criticizes academic postmodernism for legitimizing “alternative truths,” as he blames French postmodernists and American academics for dismantling trust in science, facts, and shared reality, making room for anti-vax movements, climate denialism, and conspiracy ideologies. He portrays Postmodern Relativism as a cultural accomplice in the rise of a society where “truth is what you feel” and “doing your own thing,” regardless of the consequences. Usually, such attitudes have been associated with the Left, but Andersen astutely shows how the Right (especially the far-right) has also used such a stance to promote its religious ideology, the rise of gun ownership in America, deluded conspiracy theories, and downplaying the necessity for progressive politics, which I find to be an interesting observation, as Andersen points out:

In fact, what the Left and Right respectively love and hate are mostly flip sides of the same coin minted around 1967. All the ideas we call countercultural barged onto the cultural main stage in the 1960s and ‘70s, it’s true, but what we don’t really register is that extreme Christianity, full-blown conspiracies, libertarianism, unembarrassed greed, and more [also gained ground]. Anything goes meant anything went….

The idea that finally eclipsed all competing ideas was a notion of individualism that was as old as America itself, liberty and the pursuit of happiness unbounded: Believe the dream, mistrust authority, do your own thing, find your own truth. In America from the late 1960s on, equality came to mean not just that the law should treat everyone identically but that your beliefs about anything are equally true as anyone else’s…. The 1960s enabled a deep and broad believe-anything-you-want ethos that has powered the political Right more than the Left—and that extends way beyond politics.[4]

Ken Wilber acknowledges and integrates the insights of Postmodern Relativism—particularly its cultural critique and attention to context—but he also criticizes it for its limitations, especially when it becomes “aperspectival madness” (which could be more correctly labeled as “perspectival madness” since it exhibits a dizzying array of perspectives that leads to impotence and the inability to act). Wilber has been a vehement critic of these Green relativistic tendencies and platforms, mockingly calling them “Boomeritis” (since it originated during the “Baby Boomer” generation), suggesting it is an odd mix of narcissism and anti-hierarchy, leading to a refusal to recognize valid structures of development (e.g., spiritual growth, cognitive complexity). His main complaint is that Green Postmodern Pluralism can devolve into paralysis or fragmentation when it denies the possibility of developmental hierarchies or shared values. There is a lot of truth to that view. Wilber emphasizes that every worldview (premodern, modern, postmodern) is “true but partial,” therefore, we need to “transcend-and-include: all of them to heal society and the individual. In other words, evolve consciousness. Postmodern Relativism rightly critiques oppressive structures and ethnocentrism, but it errs in rejecting universal truths, developmental stages, or holarchic integration. Consequently, he offers Integral Theory as a post-postmodern synthesis—retaining the insights of postmodern critique while restoring a developmental framework and transpersonal orientation, which is a principal topic of the Integral Life interview we shall be reviewing.

[1] “Deep Green” is a term I have taken from Tucker Walsh, “Deep AF Green: Why healthy, deeply embodied Green values are so often epically overlooked.” (Substack post, June 4, 2025).

[2] See, for example, “Republicans, Democrats, and Mystics,” in Up from Eden (1981), p. 334: “The discovery of the ultimate Whole is the only cure for unfreedom, and it is the only prescription offered by the mystics…. Men and women are potentially free because they can transcend the subject and the object and fall into unobstructed unity consciousness, prior to all worlds, but not other to all worlds. The ultimate solution to unfreedom, then, is neither Humanistic-Marxist [Green, Integral] nor Freudian-Conservative [Amber, Orange], but Buddhistic [Enlightened]: satori, moksha, wu, release, awakening, metanoia.”

[3] “Woke” began as a powerful term of social consciousness rooted in the Black struggle for justice. Over time, it entered mainstream discourse, was embraced by progressive movements, and later became politicized and polarized—with vastly different meanings depending on context and speaker.

[4] Kurt Andersen, Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire (2017), p. 174 [caps added].

One of the most intelligent, insightful and coherent discussions of Left and Right in relation to the development of consciousness I've read in a long time (considerably better than much I've seen from Wilber, by the way)

Well done!

This is a vitally important piece for understanding today’s culture wars—not just politically, but psychologically and spiritually. By framing our divisions as conflicting stages of consciousness (Amber, Orange, Green, etc.), the article moves beyond blame and partisanship to reveal deeper developmental patterns driving today’s crises. It honestly critiques both Right and Left worldviews, highlighting their strengths and shadow sides, while offering an Integral vision that transcends and includes them all. Most crucially, it reintroduces the role of spiritual realization as a necessary guide in our fractured world. This is more than analysis—it’s a map forward. Brad, your writing should be broadcast to a broader audience, and the understanding it provides needs to be put front and center on the table and platter of today's Zeitgeist.